‘Evangelion’ Creator Hideaki Anno Says Japanese Media Should Focus On Domestic Audiences, Not Overseas: “I Think It Can Be Accepted, But We Can’t Adjust On Our Side”

While many of Japan’s film, video game, and even manga studios are shifting their creative attentions towards overseas markets in the hopes of weathering the dwindling audience numbers caused by the country’s ongoing birth rate crisis, famed Neon Genesis Evangelion creator Hideaki Anno is has made it clear that he is adamantly opposed to the entire idea, as he believes that the appeal of Japanese media lies specifically in its unique cultural identity.

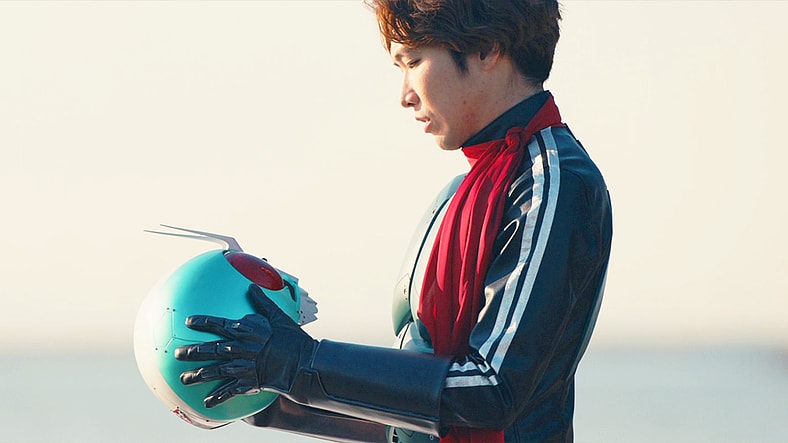

Anno, who many might also know as the director of Gunbuster, the 2004 live-action Cutie Honey adaptation, and most recently the Shin film trilogy, each entry a reimagining of a classic Japanese tokusatsu series including Shin Godzilla, Shin Ultraman, and Shin Kamen Rider, voiced his disagreement with Japan’s ongoing overseas turn during a recent conversation between himself, Godzilla: Minus One director Takashi Yamazaki, and Forbes Japan regarding the current state of the country’s entertainment industries.

Met with an opening inquiry as to whether the recent boom in global Japanese media consumption had prompted any changes in their respective production processes, Anno took the lead and explained that while “the actual production sites haven’t changed that much—consciously speaking”, the same could not be said for their industry’s general ‘demographic panic’ mentality.

“The environment may have changed, but I myself have never created a work with overseas audiences in mind,” said Anno, as machine translated by ChatGPT. “I can only make domestic things. Film companies immediately start saying “overseas, overseas,’ but personally that’s not what I’m aiming for. Basically, I focus entirely on making things that are received in Japan, things that people here find interesting, and if overseas audiences happen to find them interesting too, I’d be grateful—that’s my stance.”

With Shin Evangelion Theatrical Version [released overseas as Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time], I was the original creator and handled everything myself, from production to distribution and promotion. By making it effectively a self-produced project, no one around me could say anything, and whether it made money or not, I could take responsibility myself—that was what appealed to me. Even then, I wasn’t thinking about overseas audiences when making it. I think Yamazaki thinks about that much more than I do.”

Agreeing with his fellow Godzilla director’s own philosophy, Yamazaki likewise opined, “I think the greatest weapon for works released for overseas audiences is not thinking about overseas at all, and instead pushing the domestic aspect to its limit.”

“That gives a work strength. If you try to match global standards, there are probably many people in Hollywood who are much better at that. Instead, I think the strength of Japanese works that go overseas lies in things that are unusual—maybe a little strange, but interesting in some way. The reason Hollywood is often said to be boring lately is that formulas for “how to make a hit” have become too well established, resulting in the same kinds of works being made over and over again. Within that context, the question is how far you can go in making something domestic—not in the sense of content being Japanese, but something made with a Japanese sensibility. That, I think, is probably the most advantageous condition for us.”

Cosigning Yamazaki’s point of view, Anno declared, “That’s exactly right.”

“At least for me, my thinking is in Japanese, and I can’t do much in English beyond greetings. Works that are created through thinking in Japanese are, after all, difficult to understand except in Japanese. Film has visual and musical elements, so compared to other fields I think the language barrier is lower, but even so the dialogue is in Japanese, and it’s drama about people who move based on emotions formed through thinking in Japanese. So if there are people who can understand that, I think it can be accepted overseas, but we can’t adjust on our side. I’m sorry, but please have the audience adjust.”

“Games can still be made with interactivity in mind, but when it comes to film, it’s one-way. Viewers’ complaints don’t come back to the creators. That’s simply unavoidable. So you just have to trust the creator when they say, ‘This is what’s interesting.’ That’s why I think it’s fine for it to be domestic. Ghibli, too—[studio founder Hayao] Miyazaki makes things domestically, and I don’t think he considers overseas audiences even one millimeter. That kind of thing can be dealt with later. People who think about business should convert the work into a product and sell it.”

From there offering a final reflection on the Japanese government’s ongoing, dedicated efforts to support the production of domestic media, Anno noted, “I think the first thing that catches your eye is the money, as the export amount is greater than steel, but I think it’s good that they focused on being able to spread Japanese culture to the world at low cost, rather than money, and I think that as a country, we should value that. Korea and China are also doing it, and Hollywood was originally doing it.”