Opinion – ‘Godzilla Minus Zero’ Is Too Soon For Bringing Ghidorah Into The Equation

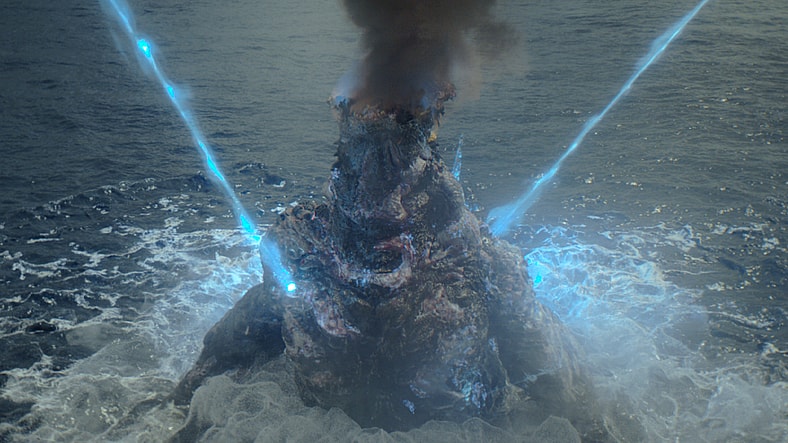

Toho has set Godzilla Minus Zero’s release date and is ramping up anticipation between fresh glimpses, such as the first poster, and possible clues social media is picking up on. Many already anticipate Godzilla and Japan will have a bigger, more formidable threat to deal with in the sequel, and it’s believed the first poster is giving away the secret of who/what that is.

RELATED: Kaiju History — Titanosaurus: The Gentle Giant Behind ‘Terror Of Mechagodzilla’s’ Legacy

Biollante and Hedorah are frequently brought up for discussion, but the color of the cloud on the poster has people considering another, more familiar, contender.

And that hypothesis, although it’s just that until we’re shown otherwise, gives me a level of apprehension for Minus Zero. Director and writer Takashi Yamazaki has proven the capability of his deft hands with his bold and grounded take on Toho’s kaiju mythos. Still, he may fumble all the good faith he has earned if he lowers himself to a tendency that became all too common in modern franchises here, there, and everywhere.

Allow me to explain:

There’s a cheap trick in franchise filmmaking that masquerades as ambition: when a story needs weight, they summon the familiar bad guy. In Godzilla’s case, when a sequel needs oomph, they resurrect the three‑headed dragon. Or when marketing needs an image, gild the creature in gold and call it destiny. I gave that trick a name – I call it ‘The Ghidorah Reflex’, and it’s become the equivalent of seasoning everything with the same spice until you can’t taste how bad or mild the food is.

If Godzilla Minus One taught us anything in 2023, it’s that restraint can be a radical act. The next film in line should not be the place to undo that lesson by defaulting to the franchise’s most overplayed hand. Minus One went big, but didn’t try to do everything at once. It kept the camera close, favored atmosphere over spectacle, and let human cost carry the weight. That choice felt like a small rebellion in a market that rewards noise.

I’m neatly brought to Ghidorah himself as an entity that is the franchise’s loudest habit. In his first few appearances, the three-headed dragon meant genuine escalation; now he’s more of a reflexive escalation button. Toho patented the formula: when you need urgency, summon Ghidorah. It’s been the refrain for 60 years across multiple eras of continuity. The result is a creature that signals corporate predictability more than narrative consequence.

That predictability is dangerous for what Toho seems to be attempting in this new era. The studio is trying to build a universe that tonally balances the intimate with the mythic – and that requires restraint as much as invention. If the next film resolves its tension by escalating to the same cosmic antagonist, its carefully crafted world becomes one‑note overnight, and audiences will notice.

They might not leave disappointed, but they’ll pick up on a pattern: small problem, medium problem, summon Ghidorah, reset – and that pattern kills curiosity by turning world‑building into a checklist rather than an organic ecosystem.

Moreover, there’s a creative laziness in defaulting to Ghidorah again. Monsters are metaphors, and metaphors must fit the story. Godzilla in the quieter entries has been a mirror for trauma and environmental hubris; Ghidorah is a metaphor for cosmic annihilation. Both are potent, but they don’t automatically stack cohesively.

For a film series that wants to be a study of grief and redemption risks thematic dissonance if it goes too Lovecraftian. The smarter move is to let each film speak for itself and let the larger universe develop to the point Ghidorah can fit, without drowning everything else out.

RELATED: Kaiju Theory: Could ‘Godzilla -0.0’ Use Hedorah To Add A Dose Of Cronenbergian Body Horror?

Practically speaking, Ghidorah demands scale. His arrival requires origin myths, global mobilization, and a script that can juggle more characters and exposition than Godzilla has time to stomp on them. That structural renovation is the opposite of what a film seeking intimacy needs.

Characters who might have been allowed to breathe become plot devices in service of spectacle (you know, like the MonsterVerse right now). The emotional center gets pushed to the margins to make room for three heads and a lot of lightning.

There’s a problem of diminishing returns, too. Each Ghidorah appearance raises the bar for spectacle, which pushes filmmakers into an arms race of brighter effects and louder set pieces. The creature risks becoming wallpaper – impressive in isolation, forgettable in context. And if his inclusion is driven by merchandising potential rather than narrative necessity, say, the art suffers.

Toho has a prime opportunity to enhance an impressive, yet still nascent, Reiwa period, only if it resists the siren song of immediate monetization and thinks long term. This isn’t an argument against Ghidorah as a concept; he’d be a fine addition to the Reiwa Minus-verse – just not right now. He’s magnificent when used in a story built to support his scale and symbolism (such as Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah).

He belongs in operatic, globe-spanning epics where his arrival is earned, and his consequences can be explored. And if Toho wants a layered, interesting universe, Ghidorah should be treated as a consequential event for the appropriate time, not the default answer to every narrative problem that barges in like bad comedy in a Showa film. Restraint is currently the bravest move.

Let the films be quieter and do their work for now. Let Minus One’s lesson about patience inform what comes next. Say no to the easy roar, and yes to the silence that lets a story breathe by keeping the hydra in the box until the story truly needs it.