Kaiju History — Titanosaurus: The Gentle Giant Behind ‘Terror Of Mechagodzilla’s’ Legacy

2025 delivered a barrage of earth‑shaking Godzilla milestones. Several classics in the King of the Monsters’ filmography – like Godzilla vs. Destoroyah, which thundered into its 30th anniversary – hit major landmarks. But few loomed larger than Terror of Mechagodzilla, turning 50 this past year. The 1975 finale for the Showa Period has only grown more formidable, as its cult reputation is swelling with every passing decade.

RELATED: Kaiju History – A Plague Of Rats Ended An Inept Production And Gave The World Gamera

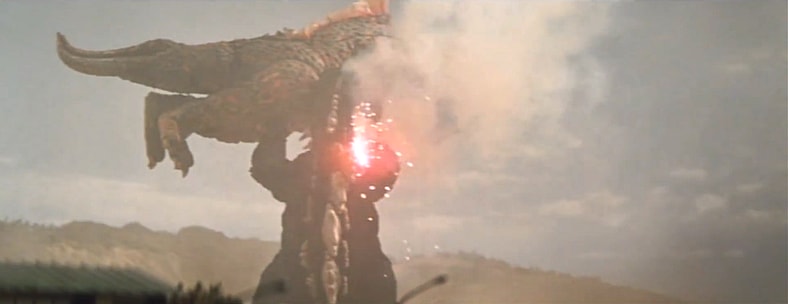

A big part of that staying power comes down to Titanosaurus, the last original antagonist introduced in the era. Unlike Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla, where Godzilla had King Caesar backing him up against his robotic double, Terror of Mechagodzilla throws him into a two‑on‑one. In the span of two films, the King goes from tag‑team victories to a straight‑up handicap match – and Titanosaurus is the reason the odds suddenly feel lopsided.

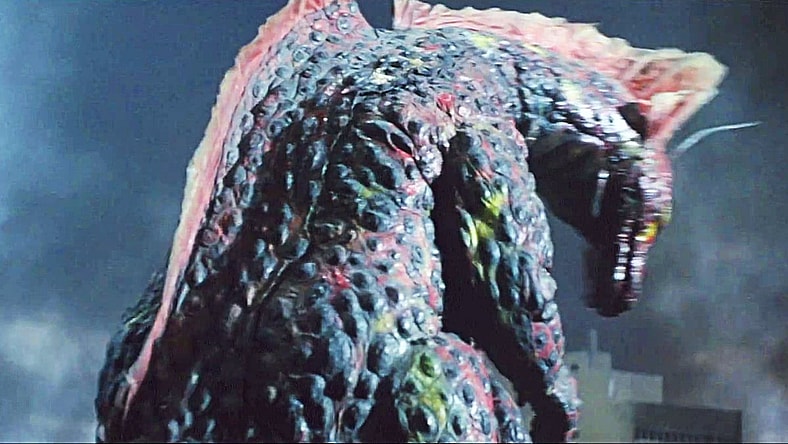

The new monster’s arc is a lot richer than just knocking over buildings and catching hands in the third act. There’s more going on under the surface as Titanosaurus isn’t your standard ‘roar, stomp, repeat’ kaiju – he’s a gentle giant dragged into a disaster he never signed up for. Between alien meddling, a scientist’s personal unraveling, and some spectacularly bad timing, he ends up weaponized against his will, less a villain and more a tragic bystander shoved into the ring.

Fans still feel for him decades later, and mind control is the real hinge of his story. Titanosaurus isn’t acting out of malice; he’s being pushed past his limits, and the movie doesn’t hide that he’s hurting because of it.

Moreover, Titanosaurus basically set the template for the controlled‑Titan trope long before it became a staple, as his loss of agency echoes through the ages of kaiju storytelling up to now. You can even see shades of it in newer monsters like Shimo, whose will gets bent by Skar King. And all of this lands harder because Titanosaurus wasn’t meant to be a bruiser in the first place.

At his core, he’s a gentle sea creature – curious and territorial, but not malicious – and that softer nature comes out in humanoid avatar Katsura Mafune (played by Tomoko Ai). She doesn’t build him, but she understands him. Katsura becomes the emotional bridge between her father’s obsession and the creature he discovered.

Her empathy is what first connects humanity to Titanosaurus, and her personal, private tragedy is what ultimately severs that bond. Without her, he’s just a misunderstood animal. With her, he becomes the heart of the film’s moral conflict.

Things get even darker once Katsura becomes a cyborg. After an accident, she’s rebuilt and immediately becomes the perfect leverage point for the Black Hole Planet 3 alien invaders, known as Simeons, from the previous film. They zero in on her father, Dr. Shinzō Mafune (played by the inimitable Akihiko Hirata, a legendary Toho player who was Serizawa back in 1954), whose long‑dismissed theory claimed sea creatures like Titanosaurus could be controlled.

Bitter and eager to be proven right, Mafune lets the simian beings stroke his ego while they quietly take over both Katsura and Titanosaurus. By the time he realizes he’s been used, his daughter and his life’s work are already under alien command.

A lot of that emotional weight comes straight from the mind behind the script: Yukiko Takayama. She was new to the industry when Toho handed her Terror, and instead of playing it safe with another loud, punch‑heavy monster romp, she wrote a story rooted in human hurt. The kaiju chaos isn’t the point; it’s the fallout.

Broken trust, manipulation, obsession… all the messy human stuff hits first, and the destruction follows. Titanosaurus, Katsura, her dad – none of them read like villains under her pen. They’re people and creatures caught in a tightening trap, and the film’s melancholy tone comes directly from Takayama choosing to write a monster movie where the real damage happens long before the city starts crumbling.

Of course, the version that made it to screen wasn’t exactly the one Takayama first turned in. Her early drafts leaned even harder into the human tragedy with more of Katsura’s inner conflict, more room for Titanosaurus’s gentler nature, and a sharper focus on the people pulling the strings. As the script went through revisions, some of those heavier ideas were trimmed or reshaped, but enough survived to give the film its unmistakable melancholy.

There is a palpable push and pull between Takayama’s more intimate vision and the studio’s need to keep things within familiar Showa boundaries.

All of this comes to a head in the film’s final stretch, where Katsura’s fate seals Titanosaurus’s own. Their stories are so tightly wound together that neither can escape the other’s tragedy, and that’s exactly the kind of ending Yukiko Takayama specialized in. She didn’t write monsters as villains; she wrote them as collateral damage in human failures.

When Katsura falls, Titanosaurus goes with her – not because he’s defeated, per se, but because the one person who ever understood him is gone. It’s a bleak note to end the Showa era on, but it’s honest in a way these films rarely allowed themselves to be. And the legacy didn’t stop there.

Decades later, Takayama returned to Titanosaurus in her manga back-up story 2075: Meister Titano’s Counterattack, giving him a quiet afterlife far removed from the chaos that defined his debut. It’s a small but telling gesture; the writer who first framed him as a victim rather than a villain couldn’t quite leave him behind.

She also made him a more active protagonist, which points back to the film’s subtle message: Titanosaurus was never really the villain. And the creature endures not because he was powerful, but because Takayama wrote him with enough humanity to make his suffering matter. In a franchise built on giants, that kind of vulnerability is rare, and it’s why this film’s shadow, and that of its “strangely innocent and tragic monster,” only grows longer with time.

Fifty years on, Terror of Mechagodzilla still hits with surprising force. Beneath the full-metal mayhem and the end‑of‑an‑era spectacle, it’s a story about people breaking things they can’t fix – themselves, each other, and the creatures caught in the crossfire.

NEXT: Godzilla: The 10 Titans We Want to See Next in the MonsterVerse And How They Get There