Opinion: Why Hollywood Doesn’t Know How To Adapt ‘Halo’

With the recent premiere of the Paramount Halo show’s second season, now seems like the time to delve into just why the series is facing fan backlash.

Let us not sugarcoat it— the first season was a disaster, and fixing its aftermath seems insurmountable. The Paramount production wears Halo like an ill-fitted Buffalo Bill skin suit, with showrunners admitting to deliberately ignoring the games.

But for all its terrible production choices, at the end of the day, one has to ask: Why?

Why does Hollywood consistently falter in capturing the essence of Halo? And why are random YouTubers who have played the games able to dissect what is wrong with the show and suggest a more fitting adaptation than the paid professionals?

The answer lies in a flawed cocktail of hubris and ignorance.

The first step in adapting anything for the screen involves a pivotal decision: picking the right genre. When crafting a screenplay for any adaptation, it’s crucial to grasp the source genre and determine the most effective way to translate it visually.

What makes Halo tricky is that it has pioneered its own genre.

What we normally think of as genres – ‘sci-fi’, ‘action’, ‘fantasy’, and ‘romance’ are actually marketing terms meant to provide a quick recap of the specific flavor of story a given work will provide its audience.

Meanwhile, when shaping a story, screenwriters think of genres in term of what type of story their work tells – such as Golden Fleece, Fish out of Water, Monster in the House, Buddy Love, and so on and so forth

These terms not only offer a deeper understanding of what a story truly is, they also carry significant implications for how a writer will tackle their character development: Fish out of Water stories require different characterizations than Golden Fleece stories, Golden Fleece stories require different characterizations than Monster in the House stories, and so on and so forth.

Between its gameplay, lore, and prose, Halo‘s overarching narrative defies simple categorization into just a single one of these ‘screenwriter genre’.

While Halo plotlines align with specific genres, the entirety of Halo demands adaptation within a novel framework.

I have coined this framework as the ‘Paleo-Cosmic Epic’.

Named in contrast to ‘Cosmic Horror’, this genre contains four pivotal elements.

And while the full details of these elements can be found in my documentary, Why No One Knows How to Adapt Halo for Screen (check it out below), for the sake of this article, we’ll be focusing on just one: the use of two-dimensional characters.

Most people conflate a poorly written three-dimensional character with a two-dimensional character, but they are actually distinct concepts.

A three-dimensional character has a ‘character spine’ that consists of a want and a need. Their transformations are internal and only occur when they overcome their ‘need’ to attain their ‘want’.

On the other hand, the transformation experienced by two-dimensional characters is external, with their pivotal midpoint revelations typically revolving around their gaining more awareness as to how their actions will affect the world rather than uncovering internal flaws.

While this two-dimensional archetype is predominantly used in serialized television series – examples of such characters include Harry Bosch, Columbo, various noir detectives, and James Bond, the last of whom consistently discovers the villain’s true plan at the story’s midpoint – it’s also embodied in video games by most player avatars.

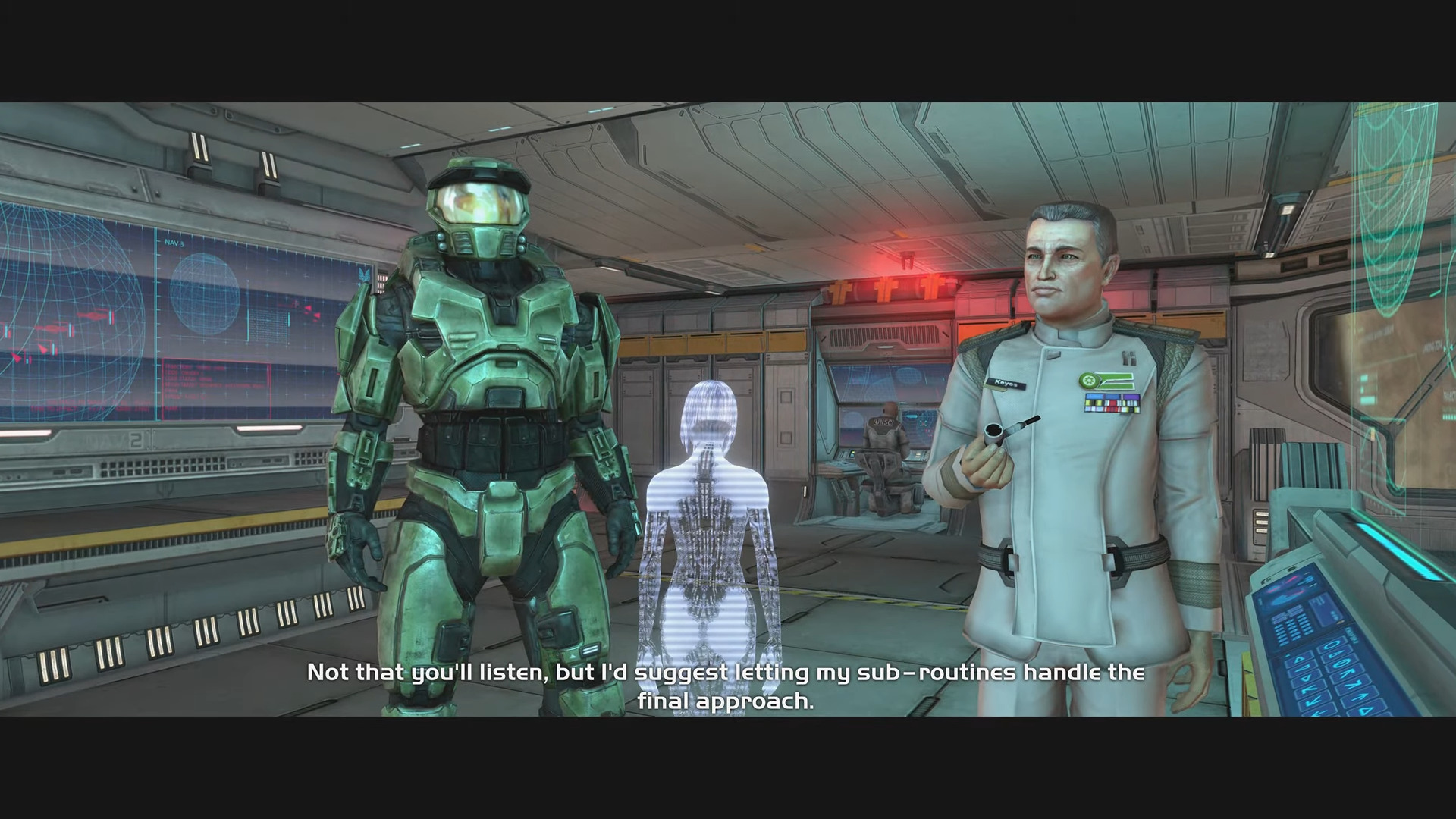

From the Master Chief to the Doom Slayer, player characters must be placed in the correct relation to all other characters in order for them to work on screen.

RELATED: Halo EP Kiki Wolfkill Says Master Chief Sex Scene Was “Important” To Series’ Story

Unfortunately, Paramount attempted to reshape the Master Chief into a three-dimensional character.

And in their eternal wisdom, they decided the best way to try and affect this change was to give him the same internal flaw a teenager with mommy issues would have – a questionable creative choice, at best.

RELATED: ‘Halo’ TV Series Star Pablo Schreiber Agrees That Master Chief Sex Scene Was A Bad Idea

The fallout from this decision to change the Chief’s base archetype will continue to infect Season 2 because of one simple problem: With every iteration, you need to give a three-dimensional character a new character spine to grapple with.

Consider the simplicity in the case of Columbo, where introducing him to a new scenario devoid of awareness restarts the narrative cycle.

In contrast, the Chief’s ongoing need for newer and newer ‘character spine’ presents a predicament which can only be solved by continually characterizing the Master Chief away from his true purpose within the Halo universe.

A more prudent approach to the Chief’s character would have been to adopt the strategy used by Godzilla Minus One, wherein Godzilla is a two-dimensional character that acts as a vector of change for the three-dimensional characters.

Coincidentally, Halo Infinite follows a similar trajectory. The Master Chief acts as a vector of change for the pilot of his downed Pelican, Fernando Esparza.

This method avoids the need to forcibly mold the character into an inappropriate framework they were never meant for, and the fans stay happy.

Unfortunately, executing such a strategy necessitates a genuine respect for the source material—an element noticeably lacking in Hollywood’s current landscape.

More About:TV Shows Video Games