Kaiju History: Godzilla Once Teamed Up With “Jesus” To Devastate Humanity In An Insane Unmade Proposal

Previously in Kaiju History, we explored Godzilla’s apocryphal duel with the Devil, so this month, we go from the Lord of Darkness to his sworn enemy, The Lord – of a sort, anyway or in a manner of speaking. In any case, I mean in the least conventional, most bonkers way imaginable.

To do that, we have to go back to the late 1970s again when the culture was at its most experimental and psychedelic artistically and socially – which is a nice way of saying everyone and everything was ‘totally baked.’

This culture had an effect on the G-Man like no other influence before or since by begetting the most insane pitches ever submitted by anyone who was seeking a studio’s approval.

Toho, eager to a fault to push the boundaries with their giant monster, had an open door for these ideas to be heard. Many of them shared an environmentally conscious or spiritual quality that echoed trends and concerns of the age, but while they may have been timely, they often didn’t get farther than a meeting or the circular file.

There was one case where such a film was made – one that painted pollution as the biggest threat to the Earth and mankind. That film was Godzilla vs. Hedorah, The Smog Monster, which divides the fandom to this very day with its tone and messaging.

In all likelihood, it was divisive within Toho as well since the director, Yoshimitsu Banno, never got to make another movie with them. A sequel to Hedorah was being developed only to be canceled, leaving the monster in limbo for decades – but that’s a story for another time.

There was no shortage of treatments similar to Banno’s, but Toho may have reached their limit with hearing them out as they got weirder and more absurd-sounding. On that note, I want to introduce you to the one that went further than any of them – even Banno and Godzilla vs. The Devil.

“God’s Godzilla” is the name of a treatment by sci-fi and alternate history author/critic Yoshio Aramaki submitted in 1979. It was a nugget in a pile of rejected proposals seeking to take up the task of reviving the King of the Monsters into a new era.

That is precisely what Aramaki’s treatment did; it began when aliens arrived from deep space (specifically from “The Null Space of the Continent of Mu”) – like they often do in Tokusatsu pictures – and landed in Peru.

This destination is no coincidence as the South American nation is home to the infamous Nazca Lines that ancient alien theorists believe were made so space travelers could see them from the sky, and find a worthy runway waiting for their ships if they ever returned.

Well, they do and it spells disaster for humanity. With some “flashing lights,” the aliens wake up a “dinosaur-shaped figure” that you can probably guess is Godzilla. Under their control, he rises to do their bidding as their weapon (or “god” as the proposal says) of mass destruction.

According to Aramaki in a translated preamble to his treatment, “This new Godzilla would wipe out the image of a grotesque future Godzilla, and I believe that this Godzilla must be both aesthetic and modern.” He added the new Godzilla “will be developed for the future,” of the 21st century “and should carry forward with it a sense of postmodernism.”

That sense of the postmodern carries with it a tendency toward assembling a pastiche of multiple influences. Some mentioned, like King Kong, are perfectly in line with Godzilla. Others including Tarzan, Frankenstein, and the French pulp antihero Fantômas are as disparate as can be.

Aramaki wanted to “imitate” characters that thrived each time they were shown to the next generation, which is a timeless mandate. However, his intro gets trippier from there as he calls upon everyone involved to “recognize the discrepancy within the grotesque, i.e. between supernaturalism and surrealism.”

They then had to exercise their imaginations and take their “thoughts to warp speed.” How would they do that? “The staff shall be trained to be able to immediately allow 4-dimensional images to come to their minds,” Aramaki explains. “Horizontal and diagonal thought as well as reversals in thought are already behind the times.”

After all that, he gets to the story and somehow still urges Toho to keep it simple. “For the story, the simpler it remains, the better it will likely be,” he wrote.

Anyway, back to his Godzilla…

Aramaki describes his Gojira as “akin to the Hindu god Kali.” “This Godzilla is not an ally of justice. In other words, he is a malevolent god, a god of destruction,” he says. “Just as Kali is a dark god, this Godzilla is truly dark.”

There is an awkward and uncomfortable mixing of religious traditions that goes with this idea. Aramaki blends aspects of Hinduism with the ancient alien theory and doesn’t stop there. After the aliens arrive in Peru and reawaken Godzilla, he brings in a Christ figure to carry out their agenda.

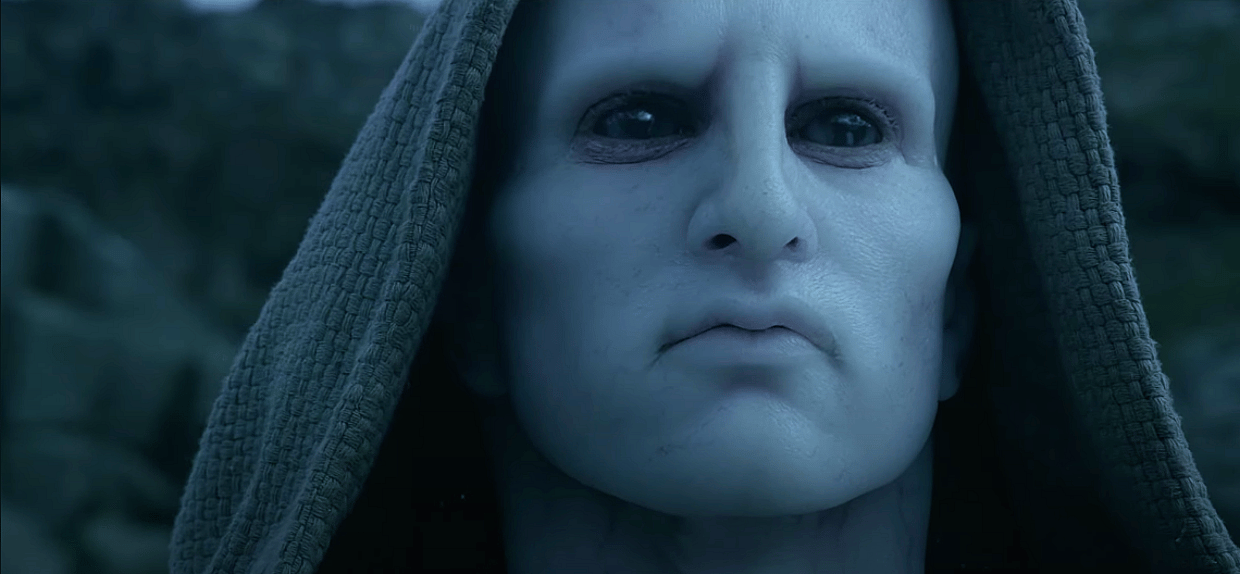

While the UN scrambles to do battle with the kaiju menace, the aliens’ humanoid emissary who identifies himself as Jesus descends, but he is not the Messiah in Scripture. Rather than calm storms and heal people, he causes chaos and plagues from nightmarish hallucinations.

Holding all the cards, he also controls Godzilla who is creating tsunamis to terrorize coastlines, but his bosses up in a spaceship take it upon themselves to go further and eradicate the Van Allen belt. This leaves the planet without protection from solar radiation.

Godzilla and space Jesus then go to Egypt where a scene of the future is depicted in the skies. It shows that life will go on, but the descendants of modern humans will be horrifically mutated and squirming. At this, Aramaki’s Christ booms “Behold, your future!!”

All is lost for humanity, Godzilla crouches like the Sphinx, the Humanoid poser Jesus, “golden and shining,” ascends back to the heavens on a stairway of light; that’s how the movie was supposed to end.

Naturally, Toho passed on this proposal. No reason was given but it’s not hard to imagine that they thought the narrative was too chaotic, and that it would offend the religious sensibilities of markets they’d try to show it in – such as the US.

The whole thing first appeared in the Japanese publication “Godzilla” Toho Special Effects Unpublished Material Archive: Producer Tomoyuki Tanaka and His Era. You can also find it on Toho Kingdom’s blog along with a few reactions. Tell us yours down below.

NEXT: Kaiju History: Godzilla Supposedly Almost Faced His Greatest Challenge In The Devil Himself