ScreenRant Claims Manga “Is Just As Political As Anything Published By Marvel Or DC,” Gets Roasted By Fans Who Know The Difference

A recent and disingenuous attempt by ScreenRant to push the tired argument that manga is “is just as political as anything published” by Western comic book publishers, specifically Marvel and DC, was met with deserved derision by fans capable of recognizing the difference between a political theme and political preaching.

ScreenRant’s poor attempt to disparage the Japanese storytelling medium, written by site comic book news editor and manga jr. lead Evan Mullicane, hit the outlet’s front page on December 19th bearing the condescending – and frankly insulting – headline “Manga Has Always Been Political, Western Readers Just Never Realized it.”

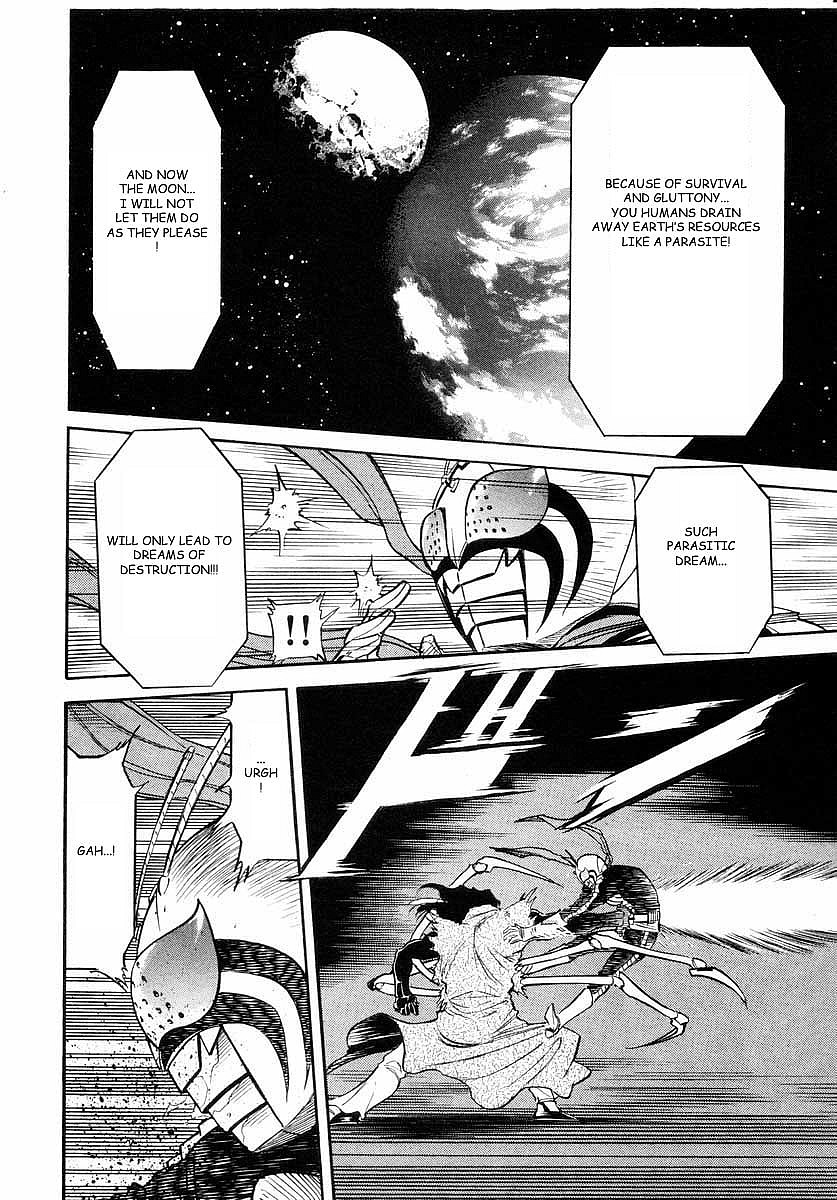

Pointing to such classic Japanese works as Astro Boy, Akira, and Nausicaä: Of the Valley of the Wind, Mullicane insists throughout his entire piece that not only was Marvel’s introduction of M.OD.A.A.K. (Mental Organism Designed As America’s King), an alternate-reality M.O.D.O.K. modeled after then-President Donald Trump, equivalent to the “deep well of political themes, messages, and imagery [that] have been present in manga since the medium’s earliest days,” but – again, insultingly – that “some of these political messages and themes are easy to ignore for less politically savvy readers.”

“All three of these classic manga used then-current events and the Japanese political landscape of their time to craft impressive and epic stories that are still influencing mangaka to this day,” wrote Mullicane, continuing to claim that in-world political themes were the exact same as blatantly taking swings at sitting politicians ala a modern SNL skit. “Looking more towards the present though, it should be equally obvious that manga creators are still using politics and social change to inform their works.”

Mullicane then turned to the criticisms of forced (and clearly activism oriented) inclusion regularly leveled towards Western comics’ addiction to putting of Western LGBTQ+ ‘diversity’ spins on classic characters – including such pleas for social media approval such as the non-binary Flash Jess Chambers or newly bisexual Jon Kent – and wondered why manga did not face the same pushback “considering that the manga industry, while far from perfect, is often on par or even ahead of the curve in including characters with a wide variety of sexualities and genders.”

Though Mullicane found himself in disbelief at how readers who criticized the pandering introduction of LGBTQ+ characters into Western books took no issue with characters such as Ghost in the Shell’s bisexual Mokoto Kusanagi or Sailor Moon’s lesbian lovers, Sailor Uranus and Sailor Neptune, the answer is clearly apparent: Western comic creators are obsessed (to a point that could easily be considered unhealthy) with centering a non-straight sexuality as the defining trait of a given character or series and insult anyone who disagrees with how it was included, whilst mangaka instead present a character’s sexuality as merely one element of their overall being and tend to refrain from shouting down fans, even if they disagree with them.

It should also be noted that, in pursuit of his argument, Mullicane attempted to push the false claim that, due to her previously ingrained use of male pronouns resulting from her father’s constant treatment of her as the son he desired – One Piece’s Yamato is transgender, despite such an idea only stemming from Western translators’ decision to take the character’s idolization of the male Oden into consideration and transcribe her neutral Japanese pronouns as male ones.

Moving to more modern works, Mullicane then conflated his own interpretation of the themes of series including One-Punch Man and Demon Slayer with the author’s own intentions – as evidenced perfectly by his assertion that “Considering the middle-eastern flare, it’s difficult not to see Fullmetal Alchemist’s Ishbalan conflict as analogous to the War in Iraq,” as, given FMA’s setting in an alternate history Germany, the fictional conflict is actually more analogous to the Herero Wars of 1904-1908.

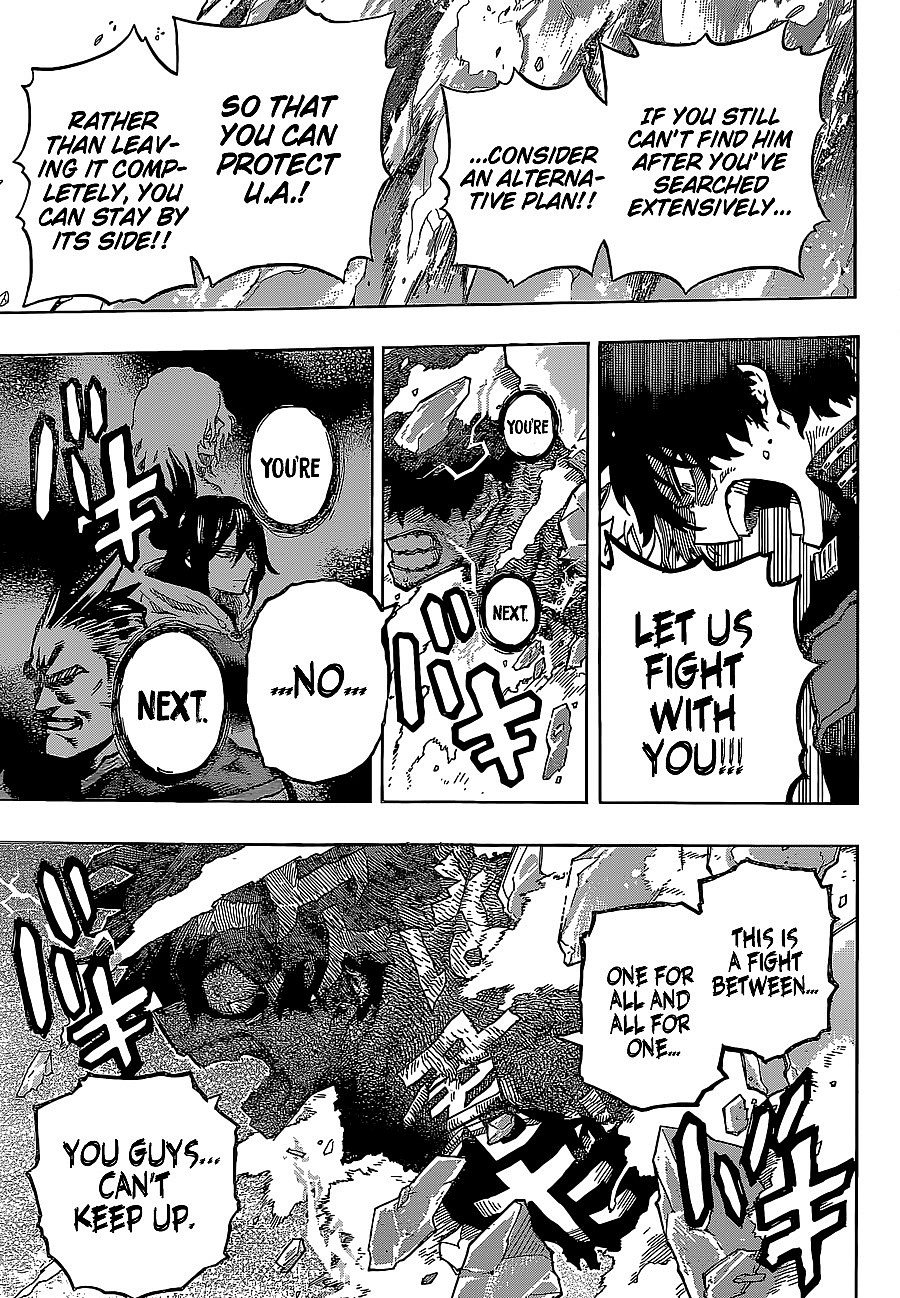

“One-Punch Man is about the hollow and unfulfilling nature of a work focused society,” said the editor. “My Hero Academia explores the pressure put on young adults to be exceptional and how that pressure can ultimately hurt and alienate those who struggle to live up to it,” while “Demon Slayer uses its Taishō era setting to examine the impact of modernization and how people adjust to a rapidly changing world.”

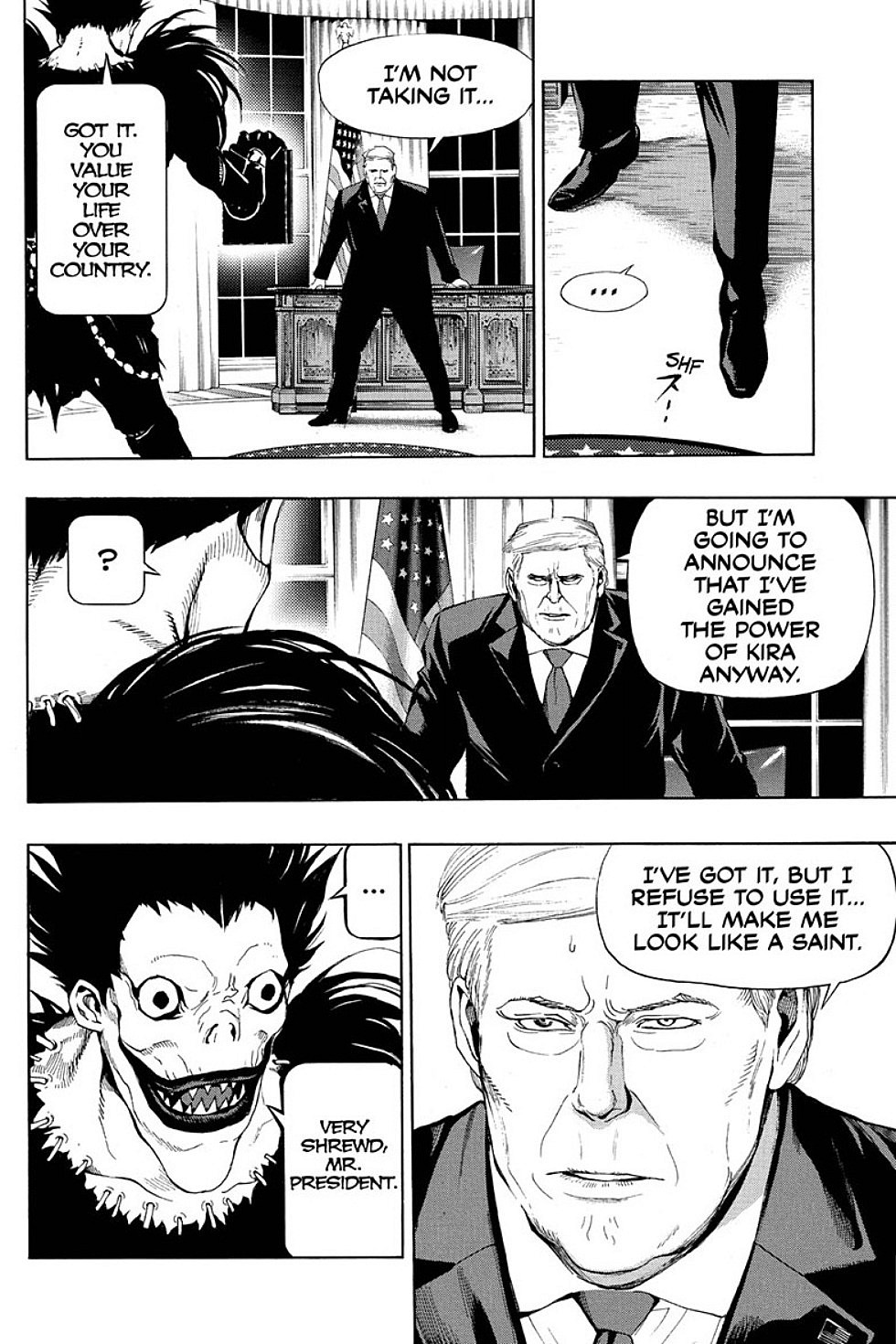

Returning to the topic of M.O.D.A.A.K., Mullicane further contended that the appearance of Trump in a 2020 Death Note one-shot was equivalent to Marvel’s groan-inducing, Reddit-cheer-drawing parody, seemingly because both works merely featured a reference to the former President.

“While some readers were complaining about Marvel turning a politician into a supervillain… Death Note was preparing to do the exact same thing with the exact same politician,” he recalled. “The series’ creators returned to the world of Death Note with The A-Kira Story, a one-shot that prominently featured a blatant parody of Trump receiving the titular Death Note and being too cowardly to use it.”

However, there is a stark difference between the two that Mullicane continues to either ignore or outright fail to see, which is the craftsmanship – or lack thereof – with which each respective example addressed the same issue.

In the Death Note one shot, while even if Trump’s appearance was a personal expression of mangakas Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata’s feelings towards the then-President, this criticism was not only limited to a few panels, but also stood as a natural ‘detour’ to the series’ overall themes of power, control, and responsibility.

Conversely, Marvel’s caricature of Trump – as well as the Spider-Gwen Annual v2 #1 story which features his only appearance – exists solely to bash him and was written with all the subtlety of an angry teenager in their first creative writing class.

Nothing clever, nothing thought provoking, just a two-page venting process which ultimately boils down to author Jason Latour’s own exhausting take of “Orange Man Bad.”

RELATED: CBR Falsely Claims That Evangelion 3.0 + 1.0 Confirms Rei Ayanami Is “Agender/Non-Binary”

Drawing his piece to a close, Mullicane proclaimed that “all of these examples should be more than enough to display that manga is just as political as anything published by Marvel or DC,” before further looking down upon readers by stating, “it’s important to note though that even series with less obvious politics are still political.”

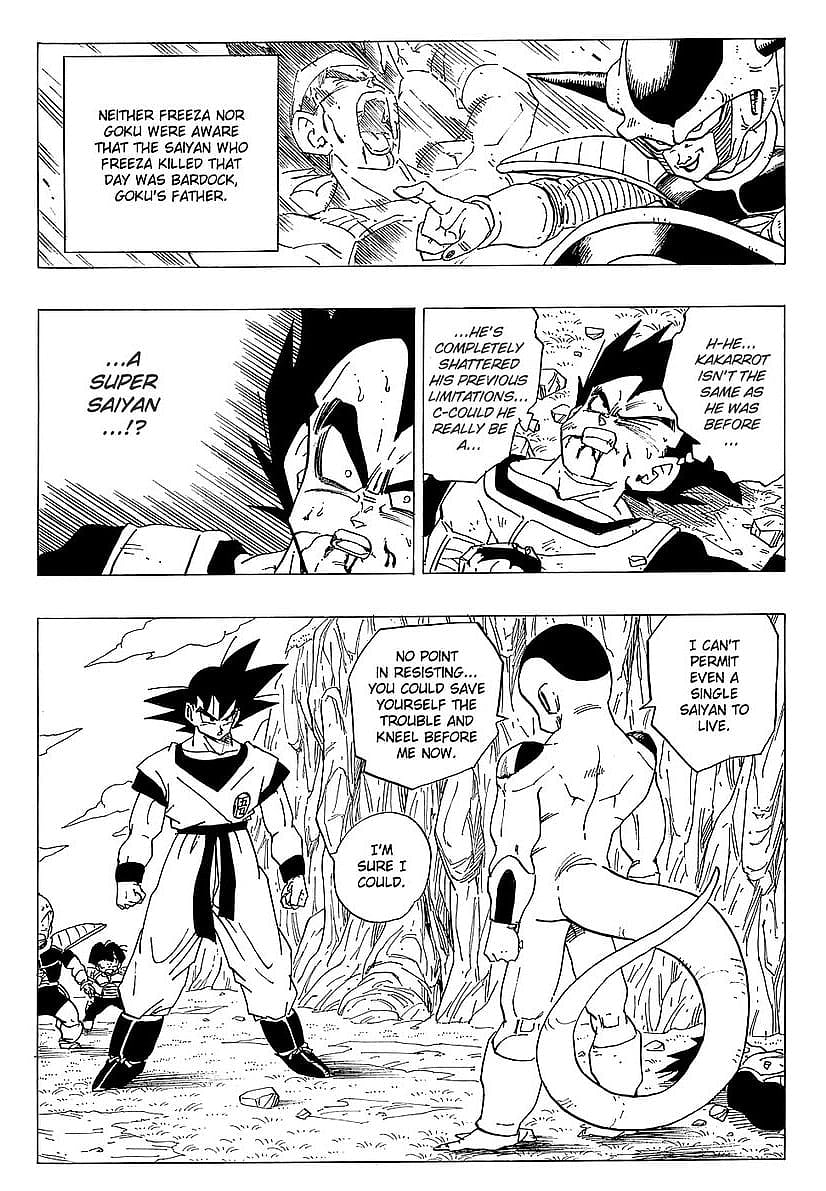

“Works like Dragon Ball might not be so forward with their politics, but they still exist in a political context and still convey political messages, whether intentional or not,” concluded Mullicane, essentially arguing that any given work is Marvel-and-DC-level political because – like anything given enough mental gymnastics – it can be read as metaphorical to real-world events.

“For better or worse, all media is political in that all media reflects the values and beliefs of the culture which created it. These themes are woven into the very DNA of their series. Saying that manga isn’t political isn’t just blatantly wrong, it’s disrespectful to the rich and textured worlds created by Japan’s greatest mangaka,” Mullicane asserted.

Unsurprisingly, given the amount of rhetorical dishonesty present throughout, the publication of ScreenRant’s article it was met with widespread mockery from manga readers, all of whom were capable of recognizing the difference between the exploration of political themes and attempts to convert readers to a certain belief.

“[The difference is] good manga, like most quality media, knows how to use political themes rather than just wedging in ‘politics’ that not only disrupt the flow of the story but also cause it age like milk,” stated @Mumboejumboh.

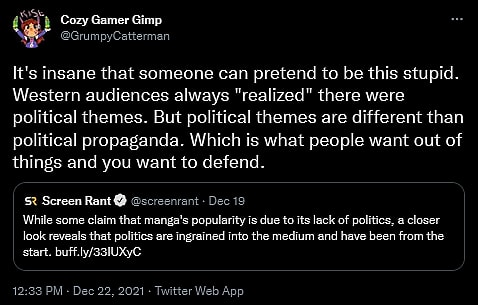

@GrumpyCatterman was taken aback by the fact that “it’s insane that someone can pretend to be this stupid.”

“Western audiences always ‘realized’ there were political themes,” he explained. “But political themes are different than political propaganda. Which is what people want out of things and you want to defend.”

Presenting an example of why more readers are turning to manga over comics, @PinkTaxEvasion drew attention to the two mediums’ different writing philosophies, comparing “Gee what’s more entertaining: ‘If we do morally incorrect thing we could end a long and tired war but we could lose ourselves in the process.’ (hypothetical plot) OR “Orange man said mean thing, we made orange man into villain without any hint of nuance.”‘

@QuestInterest similarly expounded, “‘The horrors of war’ and ‘class warfare’ and ‘the aftermath of nuclear holocausts’ are not the same themes as ‘ORANGE MAN BAD’ and ‘LET ME, WHITE WOMAN, EXPLAIN TO YOU, LATINA, HOW LATINX IS PROPER’ as well as ‘SUPERMAN PROTESTING CLIMATE CHANGE.’”

“It’s not the lack of politics,” declared @Wins98Tech. “You don’t need a f–king doctorate to see the political meaning of some of these mangas, its their ability to discuss themes subtlety without screaming at the reader and avoiding instantly dated references that ruin the story.”

“Let’s be clear,” asserted @Yun_Shoa. “An anime or manga using in world politics for flavor text and world building does not magically transform that into a political work and if you think it does you’re missing the point of whatever story the author is trying to tell.”

Ultimately, Mullicane’s argument was best and succinctly summarized by a popular tweet made by @ChristinaTasty, which itself was shared en masse in response to ScreenRant’s article.

Sharing a screenshot of an intentionally overt caricature of Trump speaking with Peter Griffin in the eleventh episode of Family Guy’s seventeenth season, ‘Trump Guy,’ @ChristinaTasty observed, “‘All games are political,’ says the extremely smart individual who can’t tell the difference between Metal Gear Solid, Bioshock, and this picture.”

What do you make of Mullicane’s argument that manga’s political themes are the exact same as those seen in Western comics? Let us know your thoughts on social media or in the comments down below!