‘The Last Unicorn’ – Why You Should Share It With Your Kids

Our children are under attack by political Left-wing zealots and radical activists attempting to indoctrinate them with ridiculous gender theory and racism training, and they’re using the media as a delivery vehicle. This has forced parents to step in and screen all available material, lest their children suffer more harm than necessary.

RELATED: Tyra Banks And Discovery+’s New Series About Child Drag Queens Opens A Disturbing Rabbit Hole

Woke corporations like Disney and Nickelodeon have been leading the charge, and they’re being aided by school teachers who are now openly expressing their sexual proclivities in the classroom, despite blowback from students and parents alike. It’s a sinister mess of hedonism and child exploitation, designed to tear them away from their mothers and fathers.

With radical Leftism now fully injected into most children’s TV shows and movies, where exactly should parents turn? The answer lies in the past, where content with good old fashioned family values can still be enjoyed by entirely new generations for years to come. One of the forgotten gems of classic children’s movies is The Last Unicorn, and here’s why you should share it with your kids.

SYNOPSIS

For those who haven’t read the 1968 novel by author Peter S. Beagle, The Last Unicorn is an animated retelling of the tale, which came out in 1982, the same decade when children’s animated fantasy films and TV shows reached a pinnacle of excellence. The popular duo Arthur Rankin Jr. and Jules Bass took over directorial and production duties to bring the story to life, with Tokyo-based Topcraft in charge of the animation.

Though it’s rather quirky and cumbersome by today’s standards, the animation and art style of the film is part of its overall charm. It may lack the fluency of modern animated films, but the sheer depth, detail and artistry in every cell is something to be appreciated.

The screenplay was written by Beagle himself, which streamlined some of his novel content for a suitable adaptation. The premise is simple – a lone Unicorn (voiced with astonishing vulnerability and honesty by Mia Farrow) learns that she is the last of her kind in the known world, prompting her to leave the safety of her forest to venture into the outside world, and learn of their fate.

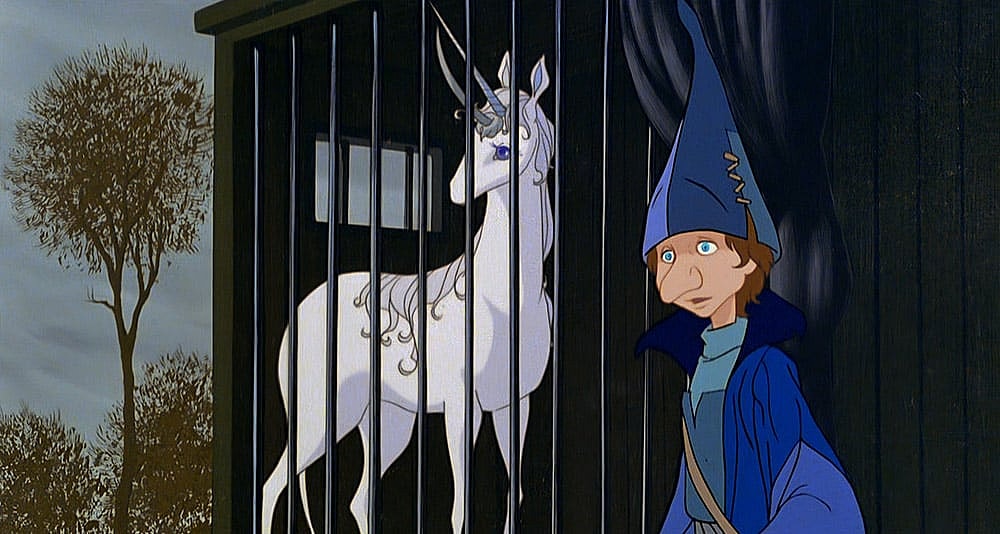

Along the way, the Unicorn learns a few things about the human world, from its loss of hope and idealism, to the evil that is bred from cynicism and selfish desires. After narrowly escaping the clutches of a sideshow witch who intends to keep her as a carnival attraction, the Unicorn teams up with two human companions who venture to a ruinous country ruled by the notoriously hermitic King Haggard.

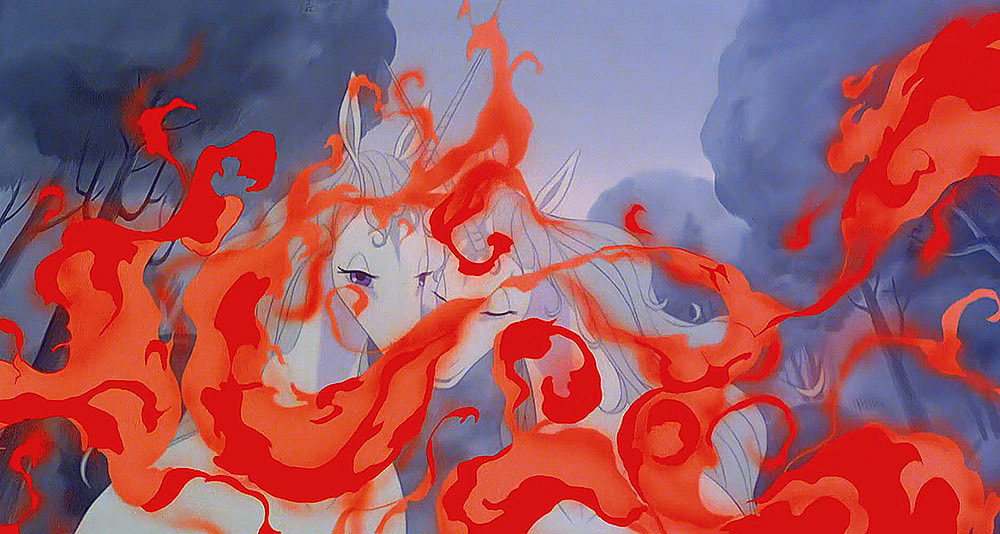

Before they can reach Haggard’s castle, a terrifying demonic entity known as the Red Bull attacks, and tries to drive the Unicorn back towards the castle. Theorizing that the Bull was responsible for the disappearance of Unicorns in the world, her ally Schmendrick the magician casts a spell which inadvertently turns her into a human woman.

Trapped inside a mortal human body, the Unicorn, now named Amalthea, begins to succumb to human imperfections and frailties. Nevertheless, the trio are welcomed by Haggard into his castle, but the King suspects that there’s more to Amalthea than meets the eye. While her companions search for clues about the whereabouts of the Unicorns, Amalthea begins to fall for the charms of the heroic and noble Prince Lir.

Soon, the Unicorn begins to have a change of heart, and allows her human desires to override the goals of her own quest. Tensions mount when King Haggard determines that Amalthea is the last of the Unicorns in the world, and his obsession threatens to destroy her, and doom the Unicorns to their permanent fate.

THEMES AND SYMBOLISM

It’s important to stress just what kind of movie The Last Unicorn is, and it’s quite easy to be misled by posters and box art. This is not a happy-go-lucky Disney film with characters breaking into boisterous song every twenty minutes, and relying on non-stop gags to keep the target audience laughing.

Neither is it “just a kids film,” or a “girl’s movie.” This is a far cry from My Little Pony.

In fact, it’s quite the opposite. The Last Unicorn is a remarkably serious and urgent film with undertones that have actual implications for the characters. It’s a somber, yet beautiful tale enriched by a sense of classic timelessness, sort of like a layer of dust that has gathered on an old photo album stored in the family attic.

RELATED: The Nacelle Company Announces Reboot Of 80s Rankin/Bass Animated Sci-Fi Series Silverhawks

The themes in the film are quite strong, and Beagle clearly knew what kind of message he wanted to convey to his audience. While obviously aimed at children, The Last Unicorn has profound lessons that will – and should – make many adults pause and give second thought to. It’s one of the most “adult” children’s films ever made.

As the central protagonist of the film, the Unicorn starts out as little more than a mythological creature blessed with immortality, and a divine aura of perfection. Yet, when she turns human, she inevitably falls victim to human imperfections, for better and worse, which is the very definition of what being human is all about.

During one point in the film, Schmendrick the magician asks the Unicorn if she feels regret, to which she replies, “I can never regret. I can feel sorrow…but it’s not the same thing.” Yet, when the Unicorn becomes human, her romance with Prince Lir leads both to a bittersweet end, and she retains human regret long after being returned to her true form.

That is an extremely powerful message for a children’s film, especially in light of peer material that refuses to venture so deep into heavy literary themes. Perhaps the strongest lesson of the story is the reality that not every ending is a happy one.

THE CHARACTERS

Supporting characters play a role in carrying other messages of great importance, as well. The evil witch Mommy Fortuna (voiced brilliantly by Murder She Wrote’s Angela Lansbury) is driven by an inferiority complex so great that she is willing to put her own life in jeopardy, just for the sake of achieving some sense of immortality.

She knows full well that one of the immortal creatures in her captivity will spell her doom, which occurs with frightening effect in the film. That creature is a terrifying and vengeful harpy, which breaks out of its cage with some help from the Unicorn, only to rain down death upon her captors. However, Mommy Fortuna accepts her fate with laughter and pride, realizing the harpy will remember captivity at her hands, until the end of time.

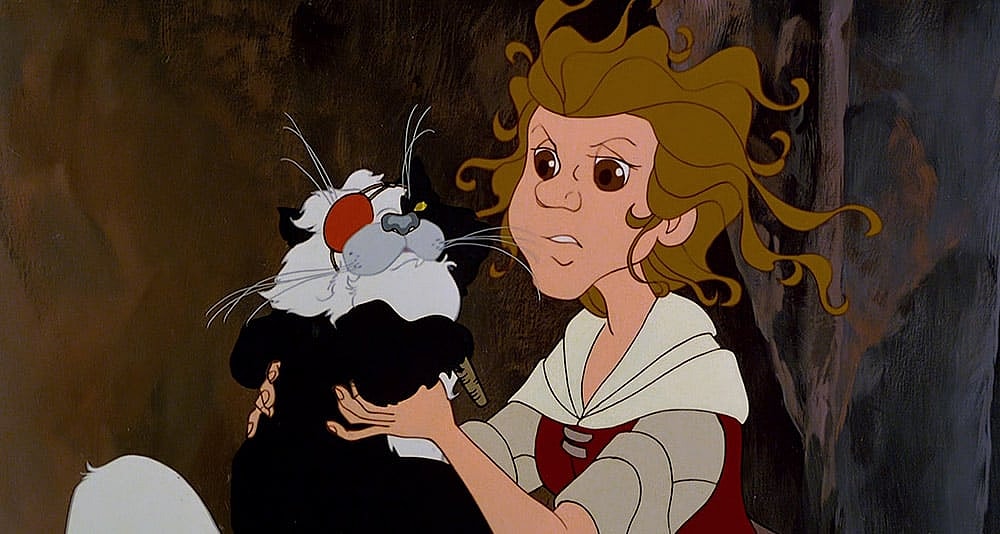

Further into the story, the Unicorn meets the crotchety, yet kind-hearted Molly Grue, who is part of a group of bandits. When Schmendrick’s magic causes chaos within the bandit ranks, Molly Grue (voiced perfectly by the incredible Tammy Grimes) decides to confront him about it, and comes face to face with a creature she only dreamt of in her youth.

Unfortunately, this exchange is very short, but it resonates strong. For Molly, the act of meeting the Unicorn so late into her years causes her to lash out in anger, demanding to know why she didn’t come to her when she was an innocent young maiden, like the stories of old. She breaks down in tears; another example of regret being a central theme in the overall story.

Next is Schmendrick (voiced by the talented and quirky Alan Arkin), whose character was altered significantly from the original novel in several key aspects. Here, Schmendrick is depicted as a bumbling magician who is considered the laughing stock among the sorcerer elite. He joined Mommy Fortuna’s carnival to ply card tricks and other gags for the amusement of the visitors.

Yet, Schmendrick has dreams of becoming a master magician, and his obsession to be taken seriously manifests itself throughout the story. Soon, Schmendrick becomes less concerned with the fate of his friends, and more on mastering the arcane arts. Though he inevitably retains his noble personality, he does so while dancing on the edge of a knife.

At the end of the film, Schmendrick manages to unleash his full power and become a true magician. When asked by the Unicorn whether that makes him happy, he replies, “Well, men don’t always know when they’re happy, but…I think so.” It’s a bittersweet and understated moment that showcases the futility of chasing a dream at the expense of the moment, and those within it.

Prince Lir (voiced by Jeff Bridges) is the odd man out in the story, and that’s what makes him so interesting. As the adopted son of the nihilistic King Haggard, one would expect Lir to be a carbon copy, but that isn’t so. Lir is his own man, driven by a need to be a hero in the face of adversity, no matter the cost.

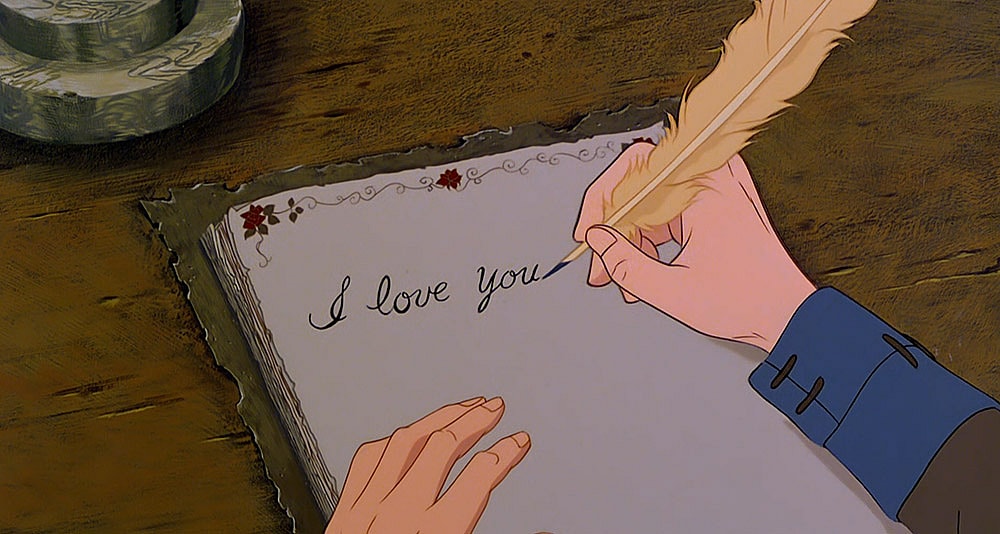

His love for Amalthea is immediate the moment he first lays eyes on her, and he spends a great deal of time trying to woo her affections by facing, as he describes it, “giants, ogres, black knights, terrible tasks….fatal riddles!” His persistence eventually pays off when Amalthea bonds with him, and she starts to forget who she is, and why she had come to the castle.

In the end, Lir is the real hero; a traditionally chivalrous and honorable male archetype who stands up for what he believes in, and the woman he loves. Not only does he sacrifice himself to try and save the Unicorn from the Red Bull’s attacks in the final act, but he is the man responsible for refusing to allow Amalthea to remain human, at the cost of her kind being imprisoned forever.

To that effect, he’s a far greater kind of hero than the ones presented in other animated films. Lir is forced to endure his own regret by giving up the one person he truly loves, simply because it’s the right thing to do. It’s his bravery and heroism that allows him to self-sacrifice for the sake of something greater than himself, or his own romantic desires.

And finally, there’s King Haggard, played by the iconic and legendary late actor Christopher Lee. It is said that Lee held a very special place in his heart for the character of Haggard, and held author Peter S. Beagle in high regard for giving him a King Lear-style character to play.

Haggard starts out looking like the typical menacing villain, but appearances are deceiving. When it is finally revealed that he is responsible for the disappearance of the Unicorns, he decides to come clean to Amalthea, recounting a story of the first time he ever laid eyes on one.

RELATED: The Most Underutilized Spider-Man Comic Book Villains

His obsessive need to possess every Unicorn in existence is bred of sheer madness, but it is driven by his tragic and sympathetic need to be happy. He displays vulnerability only once in the film when he tells Amalthea, “I like to watch them. They fill me with joy. The first time I felt it I thought I was going to die.”

He eventually reveals the reasoning for his actions, stating “I said to the Red Bull, I must have them! I must have all of them, for nothing makes me happy…but their shining, and their grace!”

Within the space of just a moment, audiences are presented with a multilayered and complex villain bound irrevocably to his own plight. Haggard fell into the throes of nihilism, depression and angst early on, and Unicorns were the only thing that ever made him feel happy. That makes him one of cinema’s most sympathetic villains; one driven by anguish and sorrow, not world domination, sadism or cruelty.

WHY YOUR CHILD SHOULD WATCH IT

The Last Unicorn is a cinematic gift that should be cherished, and watched again and again. Each year, new generations of children are introduced to it, but as time ticks by, the film is relegated further into the background. Thankfully, it still retains its cult status, and the newest Blu-Ray and digital standards have produced the highest-quality cuts of the film available.

That being said, it’s very important to make sure your child can handle the content of the film. The Last Unicorn can be dark, melancholy, and at certain moments, downright terrifying. The imagery of key characters like Mommy Fortuna, the Red Bull, and the dreaded harpy Celaeno can plague younger children with horrifying, persistent nightmares, which has been well-documented among fans.

For that reason, it’s recommended that children 8 and under should refrain from watching it until they’re older. Also, though relatively tame compared to modern standards, the proper cut of the film contains a few “hells” and “damns,” as well as three naked breasts on the harpy, which might disturb some parents.

Take heart, however. The film isn’t entirely bleak, and there’s plenty of comedic moments and laughs to be had. The humor is approached with a proper sense of balance, providing comic relief only when necessary in order to break up the foreboding tension that builds to the final act. The drunken skeleton will forever remain one of animated cinema’s most gut-busting, laugh-out-loud characters.

The Last Unicorn does what few other animated children’s films bother to do – it refuses to insult its target audience. Children are much smarter than we give them credit for, and exposing them to the story’s literary and moral themes will enrich their understanding of the world around them, while entertaining them at the same time.

Plus, it’s a magical film that will appeal to all audiences, regardless of their age, background or beliefs. This is classic fantasy storytelling with a twist – a narrative unlike any other that tells a small, centralized story, while demanding answers to some of life’s most difficult questions.

From the very first shot of a dark forest slowly creeping into view, followed by an orchestral flute paving the way for a sweeping, chorus-filled number, The Last Unicorn relies on timeless imagery and intense immersion and atmosphere to draw audiences in. For children, it’s absolutely irresistible.

There are a few elements which could subjectively be considered negatives, however. Though dated in early 1980s feel, the soundtrack by folk rock band America is still wonderful, so much so that the song “That’s All I’ve Got To Say” featured prominently in Seth MacFarlane’s modern sci-fi series The Orville.

Also, it’s clear that actors Mia Farrow and Jeff Bridges can’t sing worth a damn in the film’s few latter-act numbers, but I have always argued that this gives it a sense of authenticity and honesty lacking in Disney films. These are two characters singing their hearts out – critics be damned – based on nothing but the emotions they feel in that moment. I laud the film for refusing to go the other way.

The Last Unicorn doesn’t end on a happy note with all the conflicts wrapped up neatly with a bow. Instead, it finishes with a bittersweet culmination of events that leaves many characters unfulfilled in ways both great and small. Some might consider that a letdown, but nothing could be further from the truth.

When the final credits end, the film has come full circle, fading back into the comfortable, albeit haunting darkness of the forest it started out in. Peter S. Beagle did write a follow-up story called Two Hearts in 2004, but to many fans, the original novel is a self-contained fantasy world that needs no further exposition.

In an age when the old values are being destroyed – on purpose – in favor of freewheeling radicalism and the aimless, nihilistic pursuit of self-satisfaction, The Last Unicorn is a breath of fresh air. There’s no need to worry about Woke propaganda here. Instead, fill up the popcorn bowl, shut all the lights off, and curl up with your children while you as a family embark on 1 hour and 33 minutes worth of pure, unspoiled animated magic.

NEXT: 10 Classic 1980s Cartoon Theme Songs That Still Rock Today